|

The following is a Victory Lane article published back in 1993. It is the history of the Palliser and Winkelmann race cars as written to Dan Davis by Bob Winkelmann. We thought it a nice history of these cars.  Bob Winkelmann Bob Winkelmann The first chassis was built by Len Wimhurst at his home in London. At the time, Len was working for Brabham and his frame was undoubtedly influenced by the BT 21 suspension geometry. However, it bore little resemblance in design since the reason Len built it was to test his own theories for a more rigid structure. In a long career of race car fabrication for other manufacturers, he had developed many original details which he wanted to incorporate in one car. It is a tribute to Len's ingenuity that he was able to do this at his home. He had no bench-vice, he hack-sawed the tubing over his knee and had so little floor space that he jigged and welded the frame together on the shop wall. At this point Len approached Hugh Dibley to supply an engine and test drive the car. No name had been decided yet. Hugh entered it at Mallory Park as a TBN, (to be notified) and was sufficiently impressed with its performance that be brought a series of photographs to my house in California for a discussion on the possibilities of production. Hugh and I had been friends for some years, having competed in the USRRC (United States Road Racing Championship) in 1963 and 1964. We both served in the Royal Navy. he as a pilot, I as a flight mechanic and had joined British Overseas Airways after leaving the Navy, albeit at different periods since I left England before Hugh joined BOAC. He was, I believe, the youngest Concorde pilot and was operating London, New York, Miami, with occasional Honolulu runs which gave him the opportunity for layovers in San Francisco. The photos showed a rugged machine. Len had planned for a possible formula Libre car and it could easily handle Formula One or Chevrolet engines. All suspension rod ends were half inch, a necessary detail for off course excursions from American tracks. My experience with Lotus and other British built race cars had made me well aware or the delicacy of the frame and suspension components of most marques. Len's chassis was ideal for the U.S. market. We discussed the possibility of going into limited production. I was convinced of the need for a strong single seater. So, with Hugh’s assurance that some changes could be made to suit my six foot frame, another drawback to British cars of the day, Hugh returned to London with my initial order for three Formula B cars and formed Palliser Racing Design Ltd. Hugh's full name is Hugh Palliser Kingsley Dibley, a combination of Sir Hugh Palliser, an ancestor who commanded one of Lord Nelson’s ships, and Hugh's father, Rear Admiral Kingsley Dibley. Hugh financed the venture and became managing director. Len was a director and production manager. Hugh and I exchanged courtesy directorships in each others companies and I became sales director for the US. Since my company, Robert Winkelmann Racing Ltd., had been in business for several years and was fairly well known In the US, it was by common consent that the cars would be called Winkelmanns when sold in America. The first three Winkelmann cars were delivered in May and June of 1968 to Dan Murphy of Wisconsin, Rodolfo Junco in Texas and myself in California. Designated WD-B-1, for Wimhurst-Dibley Formula B, Mark 1. A fourth car was delivered in April 1969 to a Mr. Harris, also of Texas. During the 1968 season, a dealership was established in Texas. Registered as Winkelmann of Texas, it was headed by Rod Kennedy and Jerome Shield. Based in Austin, these gentlemen were early Formula Ford boosters and it was in no small part due to their insistence that I urged Hugh to build a car to this new formula. Len was a bit reluctant at first, believing it was a "fiddler class. for amateurs and would go nowhere. However, I went to London at the end of 1968 with firm orders for ten cars and by the time of the Racing Car Show at Earl’s Court in January 1969 Len had modified a B-1 chassis to the new class and we introduced our first Formula Ford to the public. It is pertinent to the story that or the 41 Formula Ford WD-F-1 cars manufactured in 1969, only one, number 011 was sold in the UK as a Palliser. The rest were imported, sold, registered and raced as Winkelmanns, fourteen in Texas alone where the ability to accommodate a six corn-fed cowboy was quickly recognized. I won't dwell on the successes, there were plenty and they are well documented, suffice to say that by the end of the first season, three Winkelmann drivers had either won their division or placed high enough to make the run-offs. Meanwhile, eight of the new Formula B cars, or Atlantic as it is now known, had been delivered to the States. This was the first of the wedge designs requiring the radiator to lay almost flat. These cars, designated WD-B-2, were all sold here as Winkelmanns. We had a bit of trouble with the cooling in desert temperatures and two or three different shaped noses were tried. Eventually we got that problem sorted and the Wedge was here to stay. The Formula Ford variant of this model, WD-F-2 was to be introduced in the January 1970 Racing Car Show, but by a massive effort on Len’s part, the first three WD-F-2 Winkelmanns were completed and delivered on the 22nd of November 1969 to the three Winkelmann drivers who had won spots in the American Road Race of Champions held that year at Daytona. This model was an instant success. Many well-known drivers got their start in F-2's. They are easy to drive, quite forgiving, robust by race car standards and very fast. In all, fifty WD-F-2's left the works by the front door, 45 came: to the States, sold through Winkelmann dealers of which there were now six. At the same time Palliser was also doing a brisk business in component parts and several other manufacturers used them in the construction of their own cars. Since it was also possible to deal directly with our frame supplier and purchase a replacement frame at virtually our cost, many knowledgeable race car mechanics built pirate versions of Palliser design and called them Pallisers or Winkelmanns. It will never be known how many of these cars exist, nor was it confined to Palliser. Lotus, Lola and Brabham had the same problem. However, if it is of any concern to the current owners of Palliser/ Winkelmann cars, records were kept of all the cars sold in the States and which dealers sold them. In many cases, the names of the first owners are known. Meanwhile, back in England, Vern Schuppan and Peter Lamplough were running works Pallisers, Vern in an Atlantic and Peter in a Formula Ford with Hugh occasionally taking time off from flying to tear up track records. Calls and letters from satisfied customers came from allover the States, detailing their track successes and exchanging information about ‘demon tweaks' they had discovered to improve performance. All, of course reported back to the 'works' via Telex. Len made variants for Formula Super Vee, of which 5 or 6 were sold. The WD-F-3 and WD-B-3 rolled out of the shop incorporating detail improvements such as extra knuckle clearance around the shift lever and anti-dive front “A" arms. Minor improvements, but essentially the same car. By this time, I had established a chain of dealerships consisting of very knowledgeable people, who were providing excellent support for our customers. Parts were available on an over night basis and quite a large percentage of sales were due to replacing 'corners' knocked off by off course excursions. It had been my policy to sell the cars at little above cost in order to increase the numbers sold and allow the factory to get up to speed and improve efficiency of production. Components, however, were priced to allow dealers to make a fair profit and the bottom line began to reflect this. We seemed to be on a roll but alas, the first oil crisis now loomed forcing a lot of people to sell their cars and get out of racing. Our suppliers and sub-contractors seemed to have weekly increases in price, making it difficult if not impossible for us to maintain our lists. We had earned quite a lot of dollars for Britain, but unfortunately none for ourselves. Ultimately, Hugh was forced to cease trading and close down Palliser Racing Design. To fill outstanding orders, four cars were delivered in kit form directly to our US customers. Designated WD-F4, they were the last cars officially sold. During our three years of operation, we had focused a high degree of specialized knowledge in combination with enormous enthusiasm to produce these cars. We didn’t make any money, but everyone had a lot of fun losing it. That they are still being raced after 25 years is great source or pride and pleasure. Bob Winkelmann

10 Comments

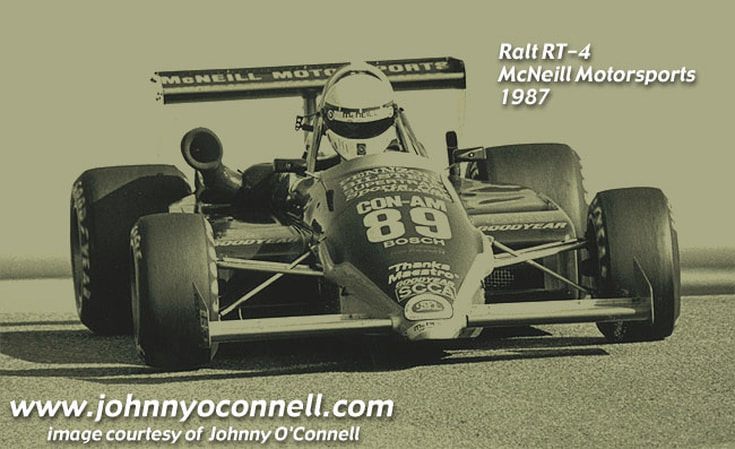

Bob Varsha hosts the final season of the Formula Super Vee at Road Atlanta on July 29, 1990. Chris Smith (USA) took the podium in his Ralt RT-5 In the early summer 18 year old Jeff Gordon tested Formula Super Vee and talked about the direction his career could take. Race Seven of the SCCA Bosch/Volkswagen Super Vee Series. Niagara Falls, New York Jun 26, 1988 Paul Radisich (NZ) wins in his Ralt RT5 Race four of the 1988 SCCA Bosch/Volkswagen Super Vee series. Indianapolis Raceway Park, May 28, 1988. Mike Smith (USA) in his Ralt RT5 took the podium. This article is from http://www.johnnyoconnell.com  Johnny O'cConnell Johnny O'cConnell At the end of my Jim Russell season in 1985, I was invited to test my first Super-Vee. For me it was a really big deal as it was a proper car, and back then super vee was the series all of the up and coming drivers were competing in. The car was the one pictured…an Anson SA-6, which was designed by Gary Anderson, who later went on to design for Jordan F-1. I remember being totally amazed by both the power and handling of the Super-vee, and I couldn’t wait to get a chance to race it. At the end of 1985, my sister met a fellow and told him about me. His name is Jerry Conrad and was without a doubt the biggest influence on my career, as he took me under his wing and helped finance my racing the next two years. In 1986 we did most of the Super-Vee series, but really had no luck with the teams we ran with. Lots of silly problems, but at that level it didn’t take much for things to not go your way. Twice we should have won races when we had mechanical problems, and then we had two second place finishes which we should have won, but had bad luck with yellow flags. Still, it was a learning experience. Going into 1987, money was tough for Jerry to spend on racing, but he told me I could sell all of our equipment, and then take the money from it and use it to go racing. We made just over $75,000 from the equipment, and I went searching. I started looking at the Formula Atlantic series, and soon hooked up with Alister McNeill. We didn’t have the full budget, but he said lets see how things go, and we would worry about money as the season went on. Well making a long story short, we won the championship, rookie of the year, and the gloysports award that was given to the driver that showed the most promise of achieving success in the sport. Alister turned out to be one of the most dedicated guys I’ve known, and he totally wanted to win just as much as I did. We had by far the smallest budget out there, but between he and our mechanic Rick Cameron, we pretty much dominated. We never even tested or anything, just showed up really prepared with one motor…that was only rebuilt once during the season. For sure it was a great year, and finally got my name to where I was starting to get noticed. One final thing about the 1987 season that was note worthy is that I got reintroduced to Bobby Rahal. I had met him when I went to Denison, his Alma Mater as well, and let him know that I was trying to get started in racing. He of course was having great success back then, and he made the mistake of saying that if he could ever do anything to help me out…just give him a call. Well needless to say, I took him up on his offer…which I’ll go over as we go further…

1984 Michigan Formula Super Vee last laps. Driver Jeff McPherson (USA) in his Ralt RT5 takes the checkered flag. 1982 Super Vee Race: Michigan,, Michigan, Sep 26-Mike Miller (USA)-Ralt RT5 Not so much a formula - more a way of life, Motorsport Magazine, January 1977 SuperVee has more to intrigue the casual reader of single-seater regulations in technical and driving terms. From the lightweight, thoroughly tuned engines that can muster 160 b.h.p. from 1-6-litres, to the agile chassis, which offers aerodynamic aids and racing tyres of reasonable width, there's enough to teach any budding World Champion the elements of his craft. Then there are the inducements of good monetary rewards (there are three Championships in Europe that a British-based competitor could fit into his calendar) and some first-class venues all across Europe. So the top contenders can live the Gipsy life that's recounted with such nostalgia by many former Formula Junior and Formula Three drivers. So, good cars, good company, good racing, why hasn't it appealed to the British? In an attempt to answer that question, and many more about the future, when water-cooling supersedes the ubiquitous aircooled flat-fours, I spent a couple of days in the company of John Morrison and his current Lola T326 SuperVee. Morrison has twice been British Champion, finished fourth in 1974's European Championship, and has even written a book about the subject. In the past he has worked for VW in this country. Now he spends his time working in a Croydon motor accessory shop or driving, including some preliminary work for Lola on their new T490 Sports 2000. Next year John and Lola will set out to take on the quick Scandinavian and European teams. They run car combinations like the Swedish Veemax chassis with £1,800 Jacktuna modified engines (Finnish driver Miki Airpainen dominated the European Volkswagen Gold Cup series with such a combination in 1976) or the German Toj with Swedish Heidegger engine. Now something of a memory in success terms are the Viennese Kaimann concern who had both Jochen Mass (1971 Gold Cup Champion) and Niki Lauda on their driving strength. Morrison simply exudes enthusiasm for the memory of driving across Europe over all kinds of challenging circuits with two primary points to discipline his pace: (1) I have no money to repair this car, (2) I have no money to go to the next race, unless I finish well up. There is no doubt in my mind that this has led to his present neat style where a minimum of fuss produces a great deal of consistent speed, an asset that looks as though it could stand him in really good stead as a test driver, whatever the racing future holds. Discussing the atmosphere generated on these continental forays John says enthusiastically, "it really is just, just, fantastic as a way of life. There are teams, men, women and even children, living with each other from track to track : you race hard, but you do not bump viciously, because— one way or another—you will not be racing the following weekend if you do. The Swedes and the Finns have these fabulous barbecues, where people just wander in and out, probably bringing their own food, music and drink contributions. The next day you may be driving round the outside of those companions, and ripe for any assault, but you really know the people, and like the GP drivers, you get to know how people will react. In fact you get to know other drivers and their personalities under stress better than your mother and father!" John agrees that he is really talking of his best seasons in Europe, and that 1976's European season was not quite as good as this in terms of knowing and trusting your opponents (in Britain our test was split into two sessions after a race incident cost John a bent corner!) but that does not stop that infectious Morrison anticipation for the battles ahead next year. Born in 1964, Formula Vee racing grew in America before emigrating back to Europe: it is still claimed to be the largest single-seater racing formula in the World. SuperVee, which amounted to building a much more recognisable racing car, without the inclusion of so many standard VW parts, had its first Championship year in 1971, both America and Europe organising lucrative series with VW backing. Today's SuperVee regulations reflect such background diplomacy and compromise that you would think they had been written by a British politician. Fortunately, they are a lot easier to understand than the souls who sit within Westminster. Basic chassis can be of monocoque or space-trame construction and the complete car must weigh a minimum of 880 lbs. The Lola is of monocoque alloy manufacture, the basic tub shared with the design used by Lola for Formula Atlantic and the Renault-engineci Formulae. Morrison recollects that the chassis cost about £3,750 at the begining of the year and is worth about £3,000 today. You can pay almost anything from £800 to £1,800 for a racing version of the VW engine. Suspension follows modern British practice around the use of wishbones of unequal length at the front; top link, twin radius rods and lower, triangulated wishbone at the rear. The Lola was supplied with Bilstein damping that mounted in unit with Lola coil springs: an anti-roll bar of 1 inch front and J inch rear is original equipment too. The regulations insist on the use of VW Type 3 (VW411) uprights, wheel hubs and brake components. This means that the fronts have to be Type 3, but at the rear, either these or Porsche 914/4 discs are interchangeable, and acceptable. VW offer a light alloy caliper concession that is incorporated as a matter of course in the Lola's specification. This light car does not require a great deal in hard anti-fade pads, and the initial "bite" can be disconcerting under wet conditions. Wheel manufacture is ungoverned, but dimensions must conform to maximum rim width of 6 in. front and 8 in. at the rear: diameter has to be within the spread 13 to 15 in. Morrison uses Minilite magnesium wheels of 13 in. diam., wearing Dunlop wet tyres for our test of 205/540 configuration at the rear, and 180/500 13 forward. It is on the engine front that the biggest differences exist between Britain and the top Europeans, John estimating the Europeans have found an additional 15 to 20 b.h.p. over the best British units, which means that the unit we tried gave little over 140 b.h.p., with maximum r.p.m. set at 7,000. Breathing arrangements for SuperVee are far more liberal than for Formula Ford 2000. Which is attractive from the driving technique viewpoint, but can naturally lead to more maintenance expense than less liberated formulae. Fuel injection is not allowed, but carburation can consist of any layout that features throttle butterfly choke sizes below 40 mm. John's Lola featured sidedraught, twin-choke carburetters when I drove it at Silverstone and twin 40 mm. Solex downdraught instruments for the later test at Oulton Park. Quite honestly the engine was transformed (the majority of the change apparently due to carburation) for the downdraught installation offered an engine as docile as a production unit with usable torque from 4,000 r.p.m. Previously the power band appeared to be exclusively concentrated around the 6,100 to 7,000 r.p.m. area. Mac Daghorn, who you would probably best remember for his brave performances in racing Cobras, modifies and maintains the power units at the village of Forrest Green in West Sussex. There is complete freedom in the profiling of camshafts and valve sizes, but the cam is unlike the rest of the engine in that you can, together with the followers and pushrods, select a manufacturer, whereas the rest of the engine has to be based around VW parts. So the finished result is an engine that is machined into a high compression, free-revving (compared to production) unit, rather than a catalogue of substitute bits and pieces. Incidentally the sidedraughts are meant to give the ultimate in power because of the direct passage their manifolding can offer from carburetter to intake port. The clutch is a modified VW unit, lining and activation to be determined in any way the constructor requires. The gearbox is a Mk 8 Hewland, which means four forward gears, reverse, no synchromesh, a normal H change pattern and VW casing. Walking around the car you have to. mentally note that the front-mounted radiator carries oil, not water. However it will not be long before water 'radiators do sprout on these VW offspring, for it is expected that the potent, and smooth, 110 b.h.p. watercooled four-cylinder will be introduced as the basic engine in 1978. For that year the waterand air-cooled power plants will compete alongside each other, then the water-cooled unit could become the sole engine in SuperVee for the following years. That is how it looks at present. Whatever happens, Lola tell us that the present car can be adapted to the new engine fairly easily, and VW care seems to be evident to ensure that competitors are not penalised much by the swop. Despite John's lanky proportions, the cockpit's neat appearance was accompanied by true comfort for the writer, once a wedge of foam had been installed. Instrumentation is confined to oil pressure (60-80 lb.), temperature of oil, rather cold at 50°C for our winter testing on wet tyres, and the current Smith's electronic tachometer. The latter isn't a patch on the old mechanically driven tachometer from Smiths, but the tooling was worn out, and the company decided that it was not economic to carry on manufacturing such units, even with their moving telltale red pointers which convicted many a driver. The new dial is much smaller, less legible and carries no pointer of any kind, even to just pre-set the r.p.m. limit. Starting was simple on the downdraught carburetters, and the extra torque was appreciated for the period that you are faced with letting the clutch in on a neccessarily tall first gear. Initially, gear-changing was accompanied by a few crunches. However I did heed John's advice to treat the car as gently as a beautiful woman! The pause between tests allowed me enough time to return td the car, and find it miraculously made into an old friend that responded so obediently on the damp and unfamiliar track that I could consistently lower my lap times without spinning. Oulton Park proved a tremendous place to test. The rates are reasonable (I think it was £8 per 2 hour session) and you only run your car on the track for that 2 hours. This means you can concentrate on driving and analysing what the car is doing—if you are John Morrison—or on working out the new sensation of the shortened track, from Cascades to Knickerbrook and a car that feels different, even amongst single-seaters. The car's balance, as you would expect from a man with so many seasons experience in SuperVee, is superb. On a wet track I found that only a few laps were needed before the light steering and torquey power output could be mated together in mild power slides around the second gear tight right that now follows Cascades: previously it was a testing lefthand, off-camber corner of great character. John proved a liberal and generous provider of laps—the first Silverstone session had to be abandoned after three or four damp laps owing to the lunch break—and he was a seasoned lap timer in the absence of usual mechanic, Christopher Smith. In the first nine laps I concentrated on drying out the path amongst the leaves and puddles, which took us from 1m. 39.68s. to 1m. 28.21s. A pause for a breather, when in racing conditions we would probably have changed over to dry tyres, and another six laps brought the times down from 1m. 27.60s, to 1m. 24.54s. The gradual progression into the art of thinking a single-seater (especially this flyweight) around a corner formed a stark contrast to the normal modified sports and saloon cars so freely offered to the press these days. In fact I have spent quite a bit of this year at the first stumbling steps in what looked to be a very interesting special stage rally car, before it was left to literally root itself upon an upturned tree stump. While a modified production car might be tolerant of a sideways approach and exit technique, a SuperVee goes faster in proportion to the effort expended keeping it smooth and straight. The object is to transmit its power more efficiently than the similarly powered buzzing bunch trying to get the better of you and your mount. Gentle movement, like that required on a high-geared power-steering system (Citroen SM, Rover 3500) has to be matched with careful use of the brakes, especially on the leafy avenue of Oulton Park. John warned me that the front would lock quite readily obviously well aware that this was the most likely way of damaging the car heavily, and that warning was merited. Arriving at the downhill swerve from left to right that follows Cascades, I simultaneously became aware that I could define the tread pattern of the N/S Dunlop and that the centre pedal was relaying that I had locked up a wheel. As the track dried and my confidence grew I found that so long as the initial application avoided the "slam-'em-on-as late as possible and try scrabbling-through" philosophy, the brakes were good. The chassis and well-matched engine make them work really hard for a living, and I could well imagine competitors with equally matched engines trying to find some improvement on this side. In this country Dunlop provide all the tyres for SuperVee and John confirmed that it was sometimes hard to get them warm enough to perform safely during Britain's long winter to winter seasons.

Initially I found good use for third gear and 4,000 r.p.m. as I learned the circuit and the car, but by the end of the session I had grown to appreciate John's statement that one would only use between 6,000 and 7,000 in racing conditions. In fact I used 5,500 to 6,500 to allow 500 for a missed gearchange, but the gearbox was a delight throughout, allowing absolutely flat-out changes to be made while accelerating, and sufficiently quick to go with hard braking down-changes on the pattern 4-3-2, or straightforward 4-2, the latter reserved for the two slowest corners on the track. Relaying the thrill of just pounding round quicker and quicker is a personal thing. The total involvement and concentration broken only as you switch the engine off, the ensuing euphoric daze broken only by John's cheerful "well, what did you think?" "Eh?" Pause to compose mind, "TERRIFIC," comes the unexpected shout of pleasure from my dried throat. Morrison steps smartly back as he persists, "but what was it like?" Mumble incoherently as I emerge from car's clasping crutch straps: struggle to subdue ego that says that I felt I was the fastest thing around a corner since Ronnie Peterson, simply replying, "on this track, it really is flying on the ground. You soar up, down, round and almost take off up Clay Hill, and under the bridge. The car only needs thinking and commiting for a corner, the chassis does the rest. "Those two apexes at Druids are tricky, but it pulls 6,500 before you get to Lodge. It doesn't seem quick in a straight line, there's still that sort of flat beat from the VW side of things, but when you put the brakes on and then try to turn into Lodge as a second gear effort, you realise how quick you were travelling. Often I felt I would just go straight on, though I only locked the wheels up once more after that first scare, but then you learn to trust how quickly the Lola really will scuttle round. "For me corners are blind that I would normally see in a saloon, but that is well compensated for by the car's response: no slop, no delay, it reacts to what you want to do. I would guess your particular car was the one to try in this respect, for it's obviously thoroughly sorted." I gabbled to a halt. Driving a road car away those impressions are redoubled by the sloppiness of road machinery and the remembered antics of production cars. Real, one man, one car, singleseater formula car selfishness bears the same relationship to Group 1 saloons as flying laden Lancaster must have felt to a Spitfire pilot. So far as Formula Vee and SuperVee are concerned in this country, further details can be obtained from Jan Bannochie, F/Vee Association, VW House, Brighton Road, Purley Surrey. They are currently working on schemes to help SuperVee Britons race their way across Europe. It struck me that those with more resources than average (financial and mechanical) might well find more pleasure/career potential in such events, rather than scratching round 10 lap FF clubbies trying to beat 500 ,others of similar inclination. J.W. We thought you might enjoy reading a period article about Autodynamics / Caldwell... |

AuthorWe have collected a number of articles & videos from a variety of sources. Please send us any historical info to us you think we should share via our CONTACT page. Archives

June 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed